Swastika: [taken from wikipedia (for the full article, click here)]

Right-facing swastika in

the decorative Hindu form,

used to evoke "shakti"

(sacred force)

the decorative Hindu form,

used to evoke "shakti"

(sacred force)

The swastika (卐) (Sanskrit: स्वस्तिक) is an equilateral cross with four arms bent at 90 degrees. The earliest archaeological evidence of swastika-shaped ornaments dates back to the Indus Valley Civilization, Ancient India as well as Classical Antiquity. Swastikas have also been used in various other ancient civilizations around the world. It remains widely used in Indian religions, specifically in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, primarily as a tantric symbol to evoke shakti or the sacred symbol of auspiciousness. The word "swastika" comes from the Sanskrit svastika - "su" meaning "good" or "auspicious," "asti" meaning "to be," and "ka" as a suffix. The swastika literally means "to be good". Or another translation can be made: "swa" is "higher self", "asti" meaning "being", and "ka" as a suffix, so the translation can be interpreted as "being with higher self".

In East Asia, the swastika is a Chinese character, defined by Kangxi Dictionary, published in 1716, as "synonym of myriad, used mostly in Buddhist classic texts",[1] by extension, the word later evolved to represent eternity and Buddhism.

The symbol has a long history in Europe reaching back to antiquity. In modern times, following a brief surge of popularity as a good luck symbol in Western culture, a swastika was adopted as a symbol of the Nazi Party of Germany in 1920, who used the swastika as a symbol of the Aryan race. After Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, a right-facing and rotated swastika was incorporated into the Nazi party flag, which was made the state flag of Germany during Nazism. Hence, the swastika has become strongly associated with Nazism and related ideologies such as fascism and white supremacism in the Western world, and is now largely stigmatized there due to the changed connotations of the symbol. Notably, it has been outlawed in Germany and other countries if used as a symbol of Nazism. Many modern political extremists and Neo-Nazi groups such as the Russian National Unity use stylized swastikas or similar symbols.

In East Asia, the swastika is a Chinese character, defined by Kangxi Dictionary, published in 1716, as "synonym of myriad, used mostly in Buddhist classic texts",[1] by extension, the word later evolved to represent eternity and Buddhism.

The symbol has a long history in Europe reaching back to antiquity. In modern times, following a brief surge of popularity as a good luck symbol in Western culture, a swastika was adopted as a symbol of the Nazi Party of Germany in 1920, who used the swastika as a symbol of the Aryan race. After Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, a right-facing and rotated swastika was incorporated into the Nazi party flag, which was made the state flag of Germany during Nazism. Hence, the swastika has become strongly associated with Nazism and related ideologies such as fascism and white supremacism in the Western world, and is now largely stigmatized there due to the changed connotations of the symbol. Notably, it has been outlawed in Germany and other countries if used as a symbol of Nazism. Many modern political extremists and Neo-Nazi groups such as the Russian National Unity use stylized swastikas or similar symbols.

Name:

Hindu child with head shaven and red

Svastika painted on it. Upanayana is a very

popular Hindu-tradition, a Samskara

or Sanskar (consecration).

Svastika painted on it. Upanayana is a very

popular Hindu-tradition, a Samskara

or Sanskar (consecration).

The word swastika came from the Sanskrit word, meaning any lucky or auspicious object, and in particular a mark made on persons and things to denote auspiciousness.

It is composed of su- meaning "good, well" and asti "to be". Suasti thus means "well-being." The suffix -ka either forms a diminutive or intensifies the verbal meaning, and suastika might thus be translated literally as "that which is associated with well-being," corresponding to "lucky charm" or "thing that is auspicious."[2] The word in this sense is first used in the Harivamsa. The Ramayana does have the word, but in an unrelated sense of "one who utters words of eulogy".

The most traditional form of the swastika's symbolization in Hinduism is that the symbol represents the purusharthas: dharma (that which makes a human a human), artha (wealth), kama (desire), and moksha (liberation). All four are needed for a full life. However, two (artha and kama) are limited and can give only limited joy. They are the two closed arms of the swastika. The other two are unlimited and are the open arms of the swastika.

The Mahabharata has the word in the sense of "the crossing of the arms or hands on the breast". Both the Mahabharata and the Ramayana also use the word in the sense of "a dish of a particular form" and "a kind of cake". The word does not occur in Vedic Sanskrit. As noted by Monier-Williams in his Sanskrit-English dictionary, according to Alexander Cunningham, its shape represents a monogram formed by interlacing of the letters of the auspicious words su-astí (svasti) written in Ashokan characters.[3]

The Sanskrit term has been in use in English since 1871, replacing gammadion (from Greek γαμμάδιον). Alternative historical English spellings of the Sanskrit phonological words with different meanings to include suastika, swastica, and svastica.

Other names for the shape are:

It is composed of su- meaning "good, well" and asti "to be". Suasti thus means "well-being." The suffix -ka either forms a diminutive or intensifies the verbal meaning, and suastika might thus be translated literally as "that which is associated with well-being," corresponding to "lucky charm" or "thing that is auspicious."[2] The word in this sense is first used in the Harivamsa. The Ramayana does have the word, but in an unrelated sense of "one who utters words of eulogy".

The most traditional form of the swastika's symbolization in Hinduism is that the symbol represents the purusharthas: dharma (that which makes a human a human), artha (wealth), kama (desire), and moksha (liberation). All four are needed for a full life. However, two (artha and kama) are limited and can give only limited joy. They are the two closed arms of the swastika. The other two are unlimited and are the open arms of the swastika.

The Mahabharata has the word in the sense of "the crossing of the arms or hands on the breast". Both the Mahabharata and the Ramayana also use the word in the sense of "a dish of a particular form" and "a kind of cake". The word does not occur in Vedic Sanskrit. As noted by Monier-Williams in his Sanskrit-English dictionary, according to Alexander Cunningham, its shape represents a monogram formed by interlacing of the letters of the auspicious words su-astí (svasti) written in Ashokan characters.[3]

The Sanskrit term has been in use in English since 1871, replacing gammadion (from Greek γαμμάδιον). Alternative historical English spellings of the Sanskrit phonological words with different meanings to include suastika, swastica, and svastica.

Other names for the shape are:

- crooked cross, hook cross or angled cross (Hebrew: צלב קרס, German: Hakenkreuz).

- cross cramponned, ~nnée, or ~nny, in heraldry, as each arm resembles a Crampon or angle-iron (German: Winkelmaßkreuz).

- fylfot, chiefly in heraldry and architecture. The term is coined in the 19th century based on a misunderstanding of a Renaissance manuscript.

- gammadion, tetragammadion (Greek: τετραγαμμάδιον), or cross gammadion (Latin: crux gammata; French: croix gammée), as each arm resembles the Greek letter Γ (gamma).

- tetraskelion (Greek: τετρασκέλιον), literally meaning "four legged", especially when composed of four conjoined legs (compare triskelion (Greek: τρισκέλιον)).

- The Tibetan swastika (࿖) is known as g.yung drung

Origin hypotheses:

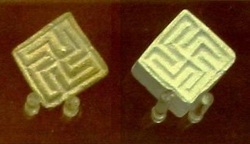

Swastika Seals from the Indus Valley

Civilization preserved at the British Museum.

Civilization preserved at the British Museum.

Among the earliest cultures utilizing swastika is the neolithic Vinča culture of South-East Europe (see Vinča symbols). More extensive use of the Swastika can be traced to Ancient India, during the Indus Valley Civilization.

The swastika is a repeating design, created by the edges of the reeds in a square basket-weave. Other theories attempt to establish a connection via cultural diffusion or an explanation along the lines of Carl Jung's collective unconscious.

The genesis of the swastika symbol is often treated in conjunction with cross symbols in general, such as the sun cross of pagan Bronze Age religion. Beyond its certain presence in the "proto-writing" symbol systems emerging in the Neolithic,[8] nothing certain is known about the symbol's origin. There are nevertheless a number of speculative hypotheses. One hypothesis is that the cross symbols and the swastika share a common origin in simply symbolizing the sun. Another hypothesis is that the 4 arms of the cross represent 4 aspects of nature - the sun, wind, water, soil. Some have said the 4 arms of cross are four seasons, where the division for 90-degree sections correspond to the solstices and equinoxes. The Hindus represent it as the Universe in our own spiral galaxy in the fore finger of Lord Vishnu. This carries most significance in establishing the creation of the Universe and the arms as 'kal' or time, a calendar that is seen to be more advanced than the lunar calendar (symbolized by the lunar crescent common to Islam) where the seasons drift from calendar year to calendar year. The luni-solar solution for correcting season drift was to intercalate an extra month in certain years to restore the lunar cycle to the solar-season cycle. The Star of David is thought to originate as a symbol of that calendar system, where the two overlapping triangles are seen to form a partition of 12 sections around the perimeter with a 13th section in the middle, representing the 12 and sometimes 13 months to a year. As such, the Christian cross, Jewish hexagram star and the Muslim crescent moon are seen to have their origins in different views regarding which calendar system is preferred for marking holy days. Groups in higher latitudes experience the seasons more strongly, offering more advantage to the calendar represented by the swastika/cross. (Note relation to the sun cross.)

Ancient Roman mosaics of La Olmeda, Spain.

Mosaic swastika in excavated Byzantine(?) church in Shavei Tzion(Israel)

Carl Sagan in his book Comet (1985) reproduces Han period Chinese manuscript (the Book of Silk, 2nd century BC) that shows comet tail varieties: most are variations on simple comet tails, but the last shows the comet nucleus with four bent arms extending from it, recalling a swastika. Sagan suggests that in antiquity a comet could have approached so close to Earth that the jets of gas streaming from it, bent by the comet's rotation, became visible, leading to the adoption of the swastika as a symbol across the world.[9] Bob Kobres in Comets and the Bronze Age Collapse (1992) contends that the swastika like comet on the Han Dynasty silk comet atlas was labeled a "long tailed pheasant star" (Di-Xing) because of its resemblance to a bird's foot or track. Kobres goes on to suggest an association of mythological birds and comets also outside China.

In Life's Other Secret (1999), Ian Stewart suggests the ubiquitous swastika pattern arises when parallel waves of neural activity sweep across the visual cortex during states of altered consciousness, producing a swirling swastika-like image, due to the way quadrants in the field of vision are mapped to opposite areas in the brain.[10]

Alexander Cunningham suggested that the Buddhist use of the shape arose from a combination of Brahmi characters abbreviating the words su astí.[3]

The swastika is a repeating design, created by the edges of the reeds in a square basket-weave. Other theories attempt to establish a connection via cultural diffusion or an explanation along the lines of Carl Jung's collective unconscious.

The genesis of the swastika symbol is often treated in conjunction with cross symbols in general, such as the sun cross of pagan Bronze Age religion. Beyond its certain presence in the "proto-writing" symbol systems emerging in the Neolithic,[8] nothing certain is known about the symbol's origin. There are nevertheless a number of speculative hypotheses. One hypothesis is that the cross symbols and the swastika share a common origin in simply symbolizing the sun. Another hypothesis is that the 4 arms of the cross represent 4 aspects of nature - the sun, wind, water, soil. Some have said the 4 arms of cross are four seasons, where the division for 90-degree sections correspond to the solstices and equinoxes. The Hindus represent it as the Universe in our own spiral galaxy in the fore finger of Lord Vishnu. This carries most significance in establishing the creation of the Universe and the arms as 'kal' or time, a calendar that is seen to be more advanced than the lunar calendar (symbolized by the lunar crescent common to Islam) where the seasons drift from calendar year to calendar year. The luni-solar solution for correcting season drift was to intercalate an extra month in certain years to restore the lunar cycle to the solar-season cycle. The Star of David is thought to originate as a symbol of that calendar system, where the two overlapping triangles are seen to form a partition of 12 sections around the perimeter with a 13th section in the middle, representing the 12 and sometimes 13 months to a year. As such, the Christian cross, Jewish hexagram star and the Muslim crescent moon are seen to have their origins in different views regarding which calendar system is preferred for marking holy days. Groups in higher latitudes experience the seasons more strongly, offering more advantage to the calendar represented by the swastika/cross. (Note relation to the sun cross.)

Ancient Roman mosaics of La Olmeda, Spain.

Mosaic swastika in excavated Byzantine(?) church in Shavei Tzion(Israel)

Carl Sagan in his book Comet (1985) reproduces Han period Chinese manuscript (the Book of Silk, 2nd century BC) that shows comet tail varieties: most are variations on simple comet tails, but the last shows the comet nucleus with four bent arms extending from it, recalling a swastika. Sagan suggests that in antiquity a comet could have approached so close to Earth that the jets of gas streaming from it, bent by the comet's rotation, became visible, leading to the adoption of the swastika as a symbol across the world.[9] Bob Kobres in Comets and the Bronze Age Collapse (1992) contends that the swastika like comet on the Han Dynasty silk comet atlas was labeled a "long tailed pheasant star" (Di-Xing) because of its resemblance to a bird's foot or track. Kobres goes on to suggest an association of mythological birds and comets also outside China.

In Life's Other Secret (1999), Ian Stewart suggests the ubiquitous swastika pattern arises when parallel waves of neural activity sweep across the visual cortex during states of altered consciousness, producing a swirling swastika-like image, due to the way quadrants in the field of vision are mapped to opposite areas in the brain.[10]

Alexander Cunningham suggested that the Buddhist use of the shape arose from a combination of Brahmi characters abbreviating the words su astí.[3]

Archaeological record:

Mosaic swastika in excavated Byzantine(?)

church in Shavei Tzion (Israel)

church in Shavei Tzion (Israel)

The earliest swastika known has been found from Mezine, Ukraine. It is carved on late paleolithic figurine of mammoth ivory, being dated as early as about 10,000 BC. It has been suggested this swastika is a stylized picture of a stork in flight.[12]

In India, Bronze Age swastika symbols were found at Lothal and Harappa, Pakistan on Indus Valley seals.[13] In England, neolithic or Bronze Age stone carvings of the symbol have been found on Ilkley Moor.

Swastikas have also been found on pottery in archaeological digs in Africa, in the area of Kush and on pottery at the Jebel Barkal temples,[14] in Iron Age designs of the northern Caucasus (Koban culture), and in Neolithic China in the Majiabang,[15] Dawenkou and Xiaoheyan cultures.[16] Other Iron Age attestations of the swastika can be associated with Indo-European cultures such as the Indo-Iranians, Celts, Greeks and Germanic peoples and Slavs.

The swastika is also seen in Egypt during the Coptic period. Textile number T.231-1923 held at the V&A Museum in London includes small swastikas in its design. This piece was found at Qau-el-Kebir, near Asyut, and is dated between AD300-600.

The Tierwirbel (the German for "animal whorl" or "whirl of animals"[17]) is a characteristic motive in Bronze Age Central Asia, the Eurasian Steppe, and later also in Iron Age Scythian and European (Baltic[18] and Germanic) culture, showing rotational symmetric arrangement of an animal motive, often four birds' heads. Even wider diffusion of this "Asiatic" theme has been proposed, to the Pacific and even North America (especially Moundville).[19]

In India, Bronze Age swastika symbols were found at Lothal and Harappa, Pakistan on Indus Valley seals.[13] In England, neolithic or Bronze Age stone carvings of the symbol have been found on Ilkley Moor.

Swastikas have also been found on pottery in archaeological digs in Africa, in the area of Kush and on pottery at the Jebel Barkal temples,[14] in Iron Age designs of the northern Caucasus (Koban culture), and in Neolithic China in the Majiabang,[15] Dawenkou and Xiaoheyan cultures.[16] Other Iron Age attestations of the swastika can be associated with Indo-European cultures such as the Indo-Iranians, Celts, Greeks and Germanic peoples and Slavs.

The swastika is also seen in Egypt during the Coptic period. Textile number T.231-1923 held at the V&A Museum in London includes small swastikas in its design. This piece was found at Qau-el-Kebir, near Asyut, and is dated between AD300-600.

The Tierwirbel (the German for "animal whorl" or "whirl of animals"[17]) is a characteristic motive in Bronze Age Central Asia, the Eurasian Steppe, and later also in Iron Age Scythian and European (Baltic[18] and Germanic) culture, showing rotational symmetric arrangement of an animal motive, often four birds' heads. Even wider diffusion of this "Asiatic" theme has been proposed, to the Pacific and even North America (especially Moundville).[19]